This is my first blog for a while. I’ve been busy finishing my degree, preparing for and sitting exams, finishing my dissertation and other course work and starting a new job. The good news is I did well. I got a first (yay!) and a full time, permanent contract at the ecological consultancy of my choice (woo!). So five years on from stepping out of the unsatisfying familiar and into the unknown I can say I’ve made it to this particular destination. From here to ecology is now from there to here and for a little while at least I’ve been enjoying the feeling of a job well done that doesn’t have ‘but it could still all go wrong’ tagged on as a wary caveat. I like to think I represent what’s possible if you apply yourself, even if you don’t consider yourself to be a natural academic.

Looking back from this vantage point at the experience as a whole, I see now that I’ve made some smart decisions along the way which have made me employable. The degree was important but without making yourself employable what use is it? So this blog is my list of tips which you may want to consider trying while you’re preparing to break into the world of ecology. They worked for me, they might work for you…

- Self belief

I’m pretty sure that if I can do it you can do it. I’m not exceptionally clever and as it turns out I’m dyslexic and dyscalculiac. I just put the hours in that’s all. If you care about your chosen field (and why wouldn’t you?) and you work hard there is no reason why you can’t make it. I’ve met some impressive, successful, skilled people who’ve told me they’re the same. You don’t need a photographic memory or to have been doing this since you were 3. Doubts are natural but don’t dwell on them. Spend your time working, not worrying, and you’ll be fine.

- Start now

Whether you’re reading this before you’ve started uni, or you’re half way through your final year, right now is the time to follow these tips. The freedom of the uni timetable makes pursuing extracurricular stuff much easier than if you’re working nine to five, and the sooner you start the more you can do, and the more you can do the more likely you are to stand out when you’re applying for jobs.

- Volunteer/join stuff

You hear it a lot. You’re probably sick of hearing it but let me explain why it’s good and what you should try to get out of it. I remembering it seeming hard to find a way in to this world of voluntary work I was being told I should enter. Before you’ve done anything ‘volunteering’ is just a word but once you’re in more opportunities present themselves.

My way in was the Lancashire Wildlife Trust. I contacted them and signed up as a volunteer. They told me about different opportunities in the region and one of them seemed doable; a conservation work party once a month at a nature reserve near Bury. For the next few years I traveled there once a month and along with the regular locals I lopped, sawed, raked and dug. I helped put up and take down the gazebos, drank tea, ate and discussed biscuits and the weather…

I did it because I’d been told I should be volunteering and I believed it was good advice but I didn’t really grasp exactly why I was doing it. I thought one day an employer would look at my CV and check I’d done some volunteering. That’s part of it but it’s skills employers are after. At Summerseat Nature Reserve I began learning to ID flowering plants. It was the place I first learned that Himalayan balsam is Himalayan balsam and what red Campion, wood sorrel and wood anemone look like (and lots more). It was a place I got to see change through the seasons and began to anticipate when the insects would return and then the birds, which plants flowered first and which ones last.

This was a really useful foundation to build upon, and the longer I did it, the more people I met in this voluntary world. They let me know about other interesting things that were happening in the region. I got invited to courses and events because I was a volunteer. Eventually I wasn’t doing things because I’d been told I should, I was developing interests in specific areas and curiosities about others I hadn’t tried yet.

If you do it right volunteering gives you transferrable skills, exposes you to new subjects and opportunities, and introduces you to nice, interesting people who can and are happy to help you. The idea of turning up somewhere on your own and meeting a load of new people might seem nerve racking at first and it’s true you may find yourself wondering what on earth you’re doing on a tram at 7am on a Sunday on your way to meet someone who’s offered you a lift to a site. It is never that bad. That anxiety always disappears as soon as you arrive and there have been so many days where I thought how glad I was I hadn’t sacked it off! After a while you get quite good at meeting new people. This is a more valuable skill than you might at first realise.

- Buddy up

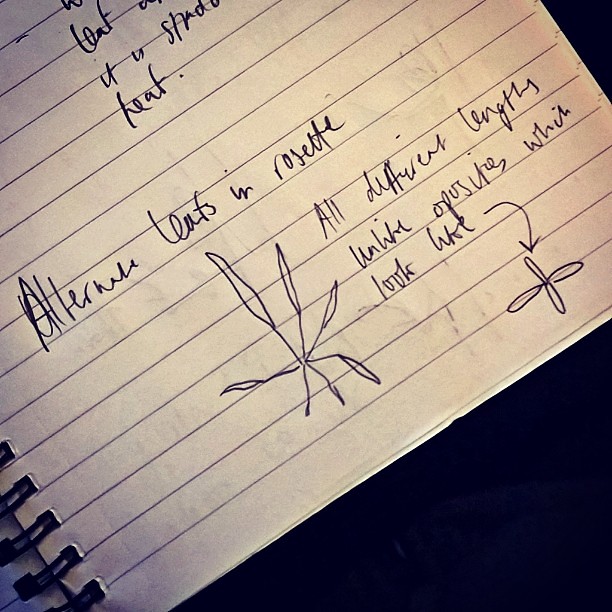

You are more likely to do stuff if you’ve arranged to do it with someone else. My partners in crime, pictured below, for the past few years have been Tom who I met on my degree and Fleur who I met at Summerseat Nature Reserve. The three of us attend courses and conservation groups together, or just meet up to practice ID’ing stuff. It’s a difficult thing to dissect but directly or indirectly I think we’ve all probably benefited professionally just by being a bit of an informal team in this way, and we are all now professional ecologists.

- Seek advice

Pick as many brains as you can. It’s a long, hard process getting the job you want but it’s pretty easy to persuade someone to have a chat with you and ask their advice on what you can do to make getting the job you want more likely. Most of the smart decisions I have made which have made me more employable have been me acting on someone’s advice.

- Act on it

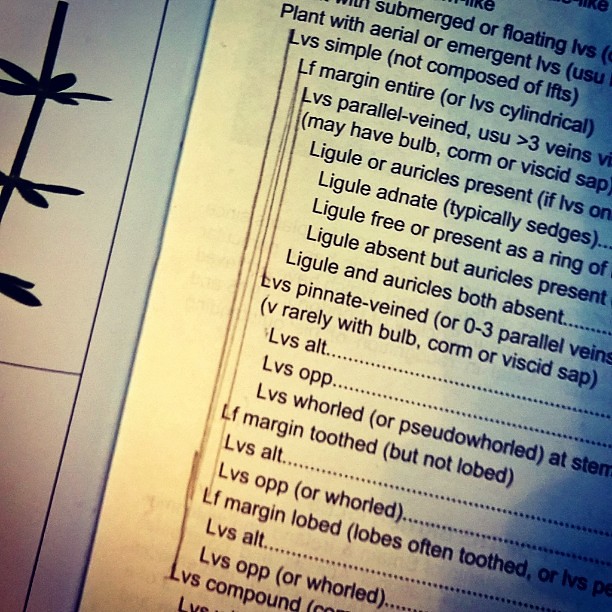

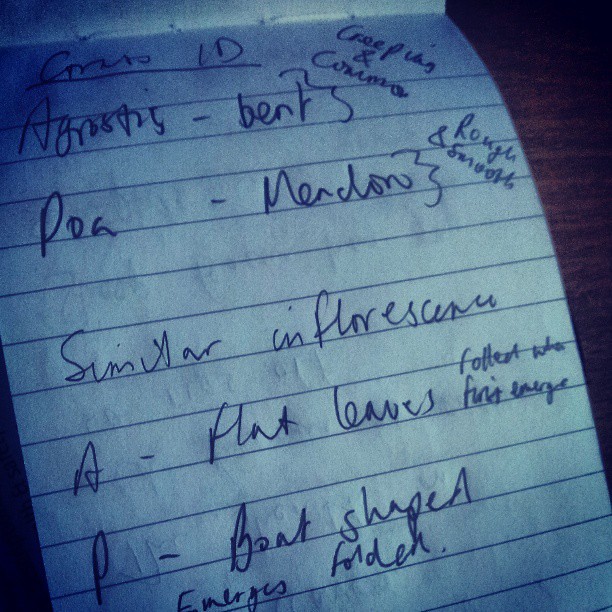

There’s something in a lot of us that feels more comfortable intending to take someone’s advice in the future, rather than acting on it right now. Anticipation Vs Experience. A local ecologist I met through the uni’s mentoring scheme in my foundation year gave me some of the most useful advice I’ve received during my uni experience. “Can you drive?” was his first question. You can’t be an ecologist without a driving licence and you might not pass first time so it’s a good idea to get your driving licence as soon as you can. He also suggested I attend the FSC (Field Studies Council) ‘Using a Flora’ course, join my local bat group and amphibian group and start working towards my bat and newt licences. I took it all and it’s played a big part in job interviews. Working towards gaining EPS (European Protected Species) licenses and becoming proficient in using flora keys is a lengthy process so why wait? It definitely helped me get the placement I wanted.

- Do a placement

If you can’t do a placement, sort out structured work experience for the holidays. Personally the year I spent in industry was the most useful thing I’ve done. It’s easier to get a placement somewhere than it is to get a job there. So you can end up working somewhere for a year that many professionals would love to work but can’t. You get to do the job you hope to end up in, so you enter the job market when you finish your studies with a degree AND experience. Employers love experience. You’ll find it easier to get a placement if you have some skills to offer, which you can gain through volunteering (see tip 3). So either through a structured placement year programme or independently, arrange some kind of work experience, and make it count. Like volunteering it’s not a box ticking exercise. Employers will want to know what you can do so make sure you learn from the people you work with and leave with a level of proficiency at actually doing the job. Aim to impress. Be a sponge.

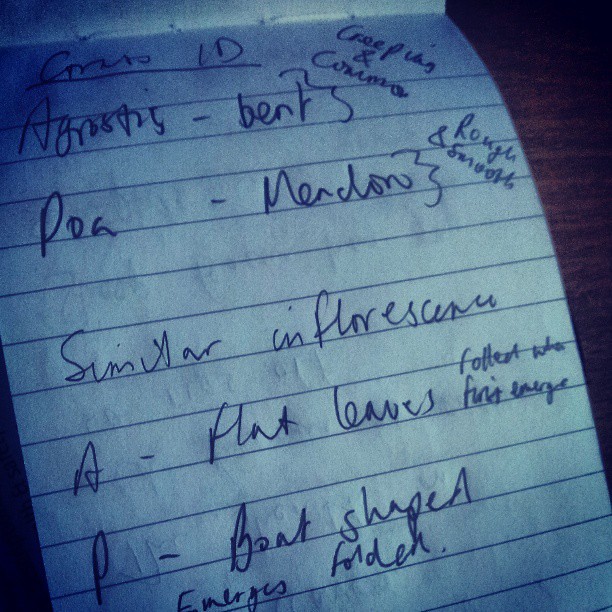

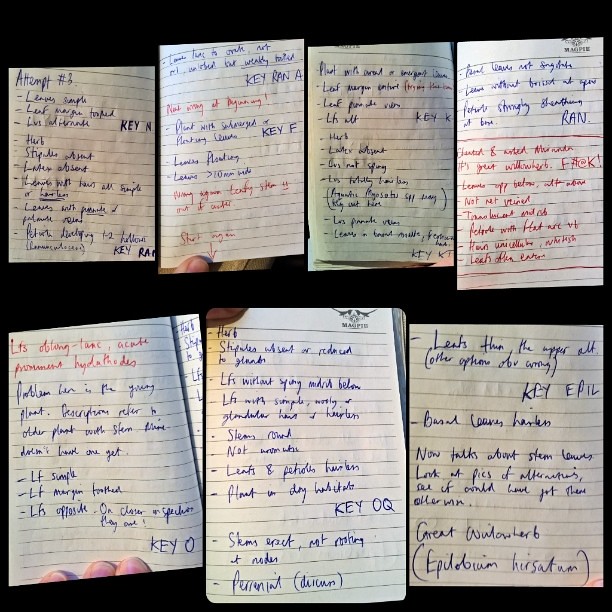

- Work on your ID skills

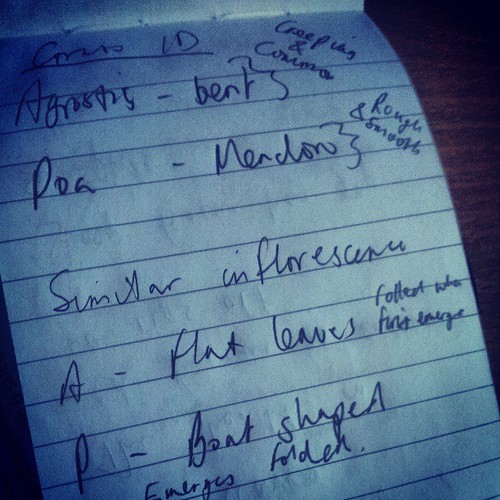

It’s not a main focus in uni so it’s up to you to learn what is what and why. It can seem intimidating but you’ll be amazed how much you learn when you look back at yourself a year ago and see what you’ve achieved if you set your mind to it. Don’t be in a rush, you’ll never learn everything, there isn’t time. Don’t get freaked out when you meet someone who can ID every grass, rush and sedge going. They’ve been at it for years. If you learn a new species a week you’ll know hundreds in a few years, the more you learn the easier it gets and the more you’ll be able to ID.

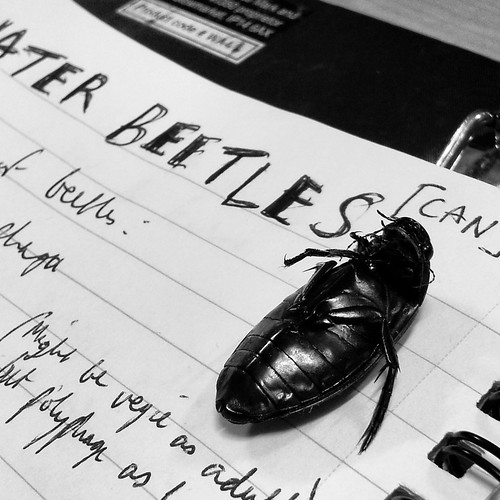

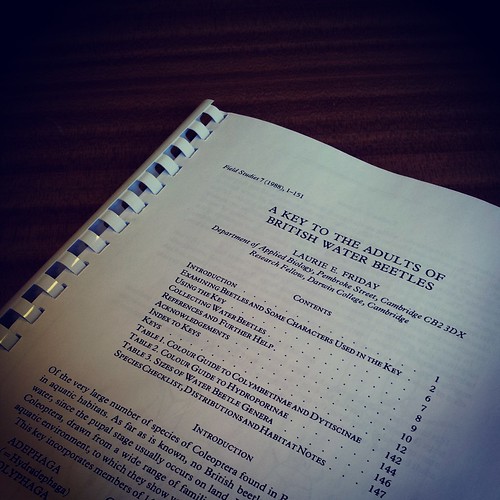

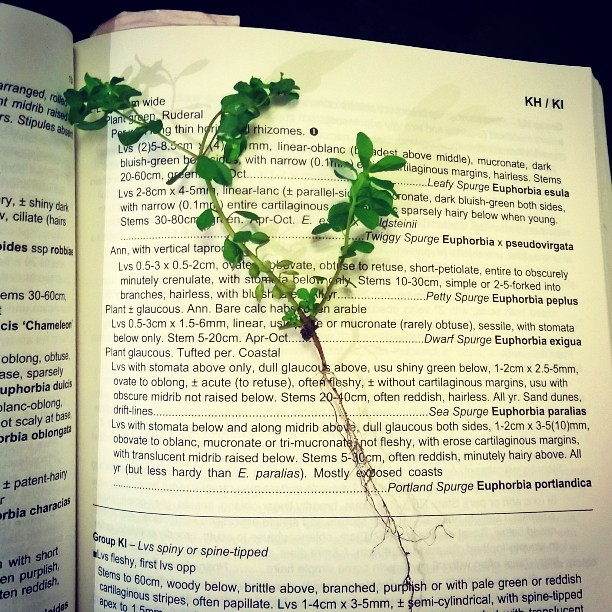

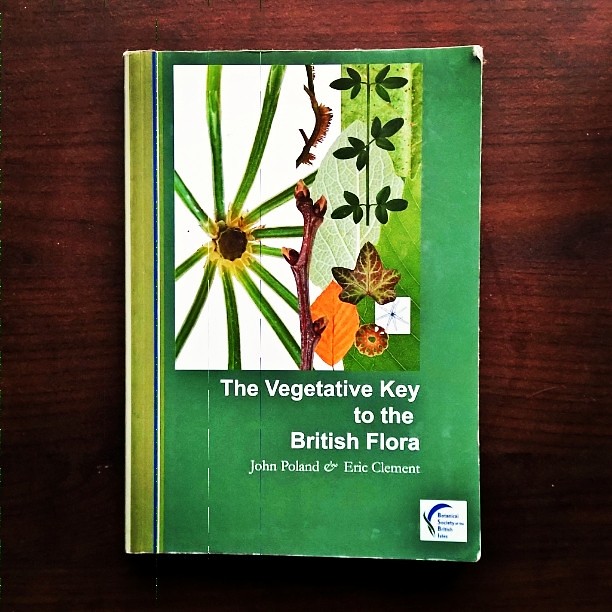

Learn to use a key. Buy a hand lens, they’re only a few quid online. Attend every ID course you hear about, there are lots of free/cheap ones if you’re in wildlife groups. Don’t worry if it doesn’t sink in straight away, just keep at it. There’s help out there. Facebook and Twitter have groups for everything you can think of and they’re often more than happy to help you out with an ID for something you’re stuck on. Take photos and put them on Flickr, Instagram etc. It becomes a useful reference. The more you can ID the more fun it gets. There is nothing better than knowing what things are.

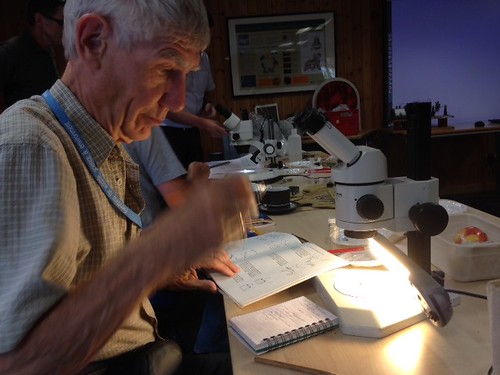

- Do extra courses

Uni holidays are long so try and fit a course in if you can. They can be expensive but sometimes grants are available to help aspiring biological recorders. Check out the FSC, CIEEM, BSBI websites. There are some excellent courses available taught by world class tutors in beautiful surroundings. You meet interesting people and get all inspired, it’s great. There’s often cake too.

Most wildlife groups run their own courses for members too. Having paid your subscription these are often free. Most areas have their own bat, mammal, reptile and amphibian, bird, botany and generalist groups. Google them.

- Interviews

If you do all that you’ll definitely be more employable. Hopefully you’ll be the most employable person that gets interviewed by the employers you want to work for, but it counts for very little if you don’t communicate it in your interview. If you’re obviously passionate and enthusiastic about ecology, or whatever your chosen field is, you are more likely to get the job. And if you’ve spent the last 3-5 years throwing yourself into this, meeting people, trying things and developing your ID and survey skills, it will come across in your interviews. If you find interviews hard, seek out someone who will give you a mock interview and honest feedback. If the idea of that you with anxiety then it will probably really help and you should definitely do it.

So that’s that. Call center monkey to ecology graduate and professional ecologist is 5 years. Whatever stage you’re at now: first year, final year, or sat at your desk wondering if if there’s more to life, I wish you the best of luck.

I hope you enjoyed this blog. If you have any questions or suggestions drop me a message. I’ll still be blogging now I’ve gone pro! But as it’s the start of a new chapter a few thank yous to; my lecturers at Manchester Metropolitan University, The volunteers at Summerseat Nature Reserve and staff at the Lancashire Wildlife Trust, Cheshire Active Naturalists, South Lancs Bat Group, the Lancashire branch of Butterfly Conservation, BSBI training and education grants, Field Studies Council, Penny Anderson Associates, NLG Ecology, and my wife Stacey. All of who helped a little or a lot, and combined got me where I wanted to be.

![2013-09-03 15.33.13[1]](https://farm6.staticflickr.com/5492/9772161692_ae22f72b88.jpg)